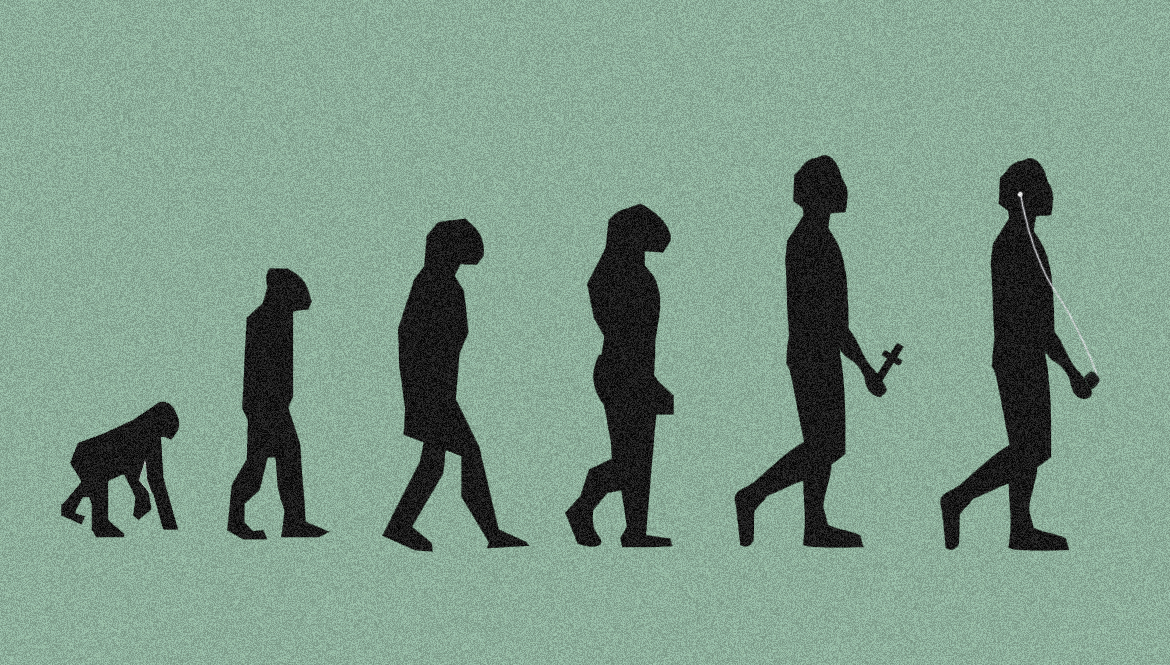

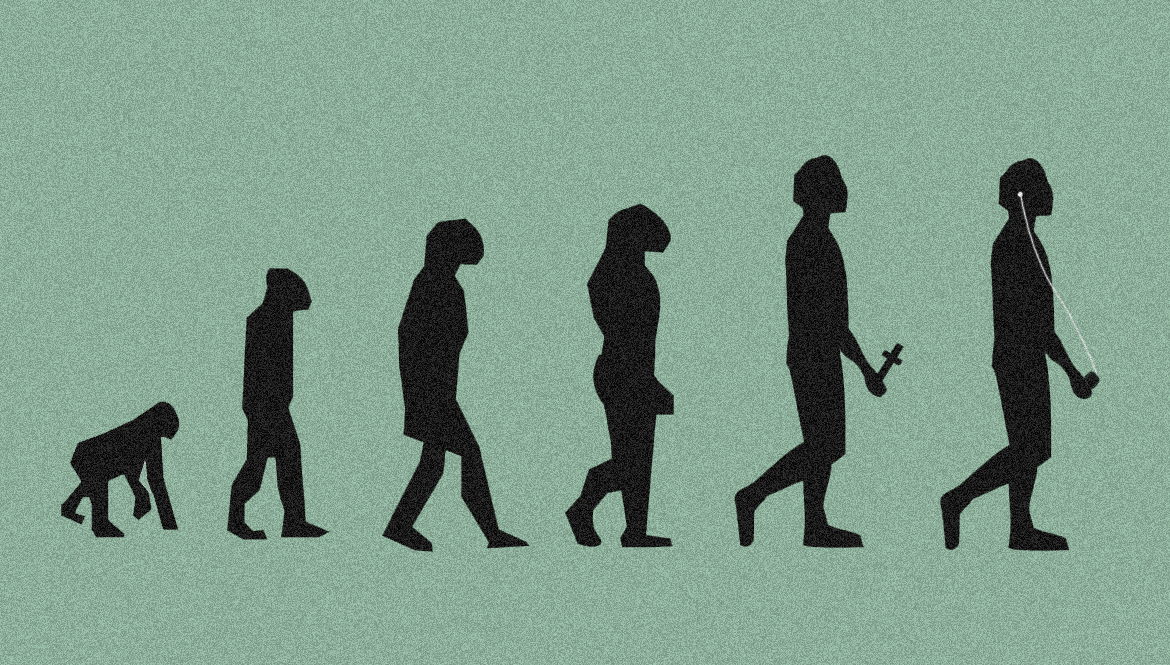

I love thinking about evolution. It explains so much, not just about how we’re built, but how we think and feel. After millions of years of it, we find ourselves living in the modern world guided, and misguided, by traits that were formed in the wild.

Take our fear of death (please). Evolution makes it easy to understand. Those creatures who did not fear death (who didn’t value themselves) did not do enough to avoid it. They were constantly jumping off cliffs or eating fire or mouthing off to creatures much bigger than them and so made their kind extinct. What survives and endures, then, is largely fearful (and egoistic).

Even with a healthy survival instinct, death is inevitable, and it’s all around. Once our intelligence evolved enough to make the mental leap from the death of other creatures around us to the anticipation of our own death, we were left with awareness of a threat we had been bred to be terrified by. No one can function in a constant state of terror, so people naturally had to dream up ways to shut out the bad news nature kept bringing. The dreams were many and varied—ghosts, reincarnation, and finally, heaven—but they all said the same thing:

We will not die. No worries.

So religion, which tends to deny evolution, is actually a result of it.

It was thousands of years more before evolution would begin to be noticed and understood. Humanity is still overcoming its resistance to these simple, natural, but—because of the thinking they follow—revolutionary ideas. The Scopes Monkey Trial may be the definitive story of our age. I, writing this, am far from literate on the subject of evolution. I was taught of God and Heaven long before Darwin.

Though some who value science are disheartened by the sway superstition continues to hold, it seems perfectly natural to me. In the fight for our belief between what is and what we wish for, is it any wonder that truth has an uphill battle? If anything, we should take pride in the great strides reason has made in the last two centuries, a minuscule period in human history. Before this time, science offered little to compete with religion’s comforts. Before science cured polio, religion at least helped us bear it. What’s impressive is how many adherents science had before its fruits had ripened. (Though back then, science did not as obviously conflict with religion. Even Galileo believed in God.)

And the scientist’s pursuit of truth may come from motives as base as the mystic’s flight from it, indeed the very same motive – to conquer nature lest it conquer us. It may be more with medicine and machinery now, and less with denial, but we’re still fighting death.

In the long run, religion may be seen as the temporary balm that helped us struggle on in the face of our fears until we had learned enough about nature to handle it with some facility; a necessary step in the ascent of human thought; not an enemy of science, but its vanguard.

June 6, 1998

Note: For a more nuanced discussion of some of these issues, try Freud’s The Future of an Illusion. It’s dense, but rewarding.